This is the last guest post from Robin Cappuccino’s travel series of his recent visit to all of the Child Haven homes – here are some thoughts from road.

Kem cho from our Child Haven Home for 49 formerly destitute children in Gandhinagar, Gujarat. As we drive to the Home, camels, goats, water buffalo, Brahman cattle, and small horses share the roadway. A mongoose crossed the road on our last visit.

Our new Home in Meu, an hour and a half drive from our current homes in Gandhinagar is nearing completion. This is great news. Our boys and girls have been in separate locations for the past several years since we couldn’t find a home large enough to keep them together. This has worked OK, but it has made staffing and coordination much more challenging. Everyone is excited to move to the new Home this spring.

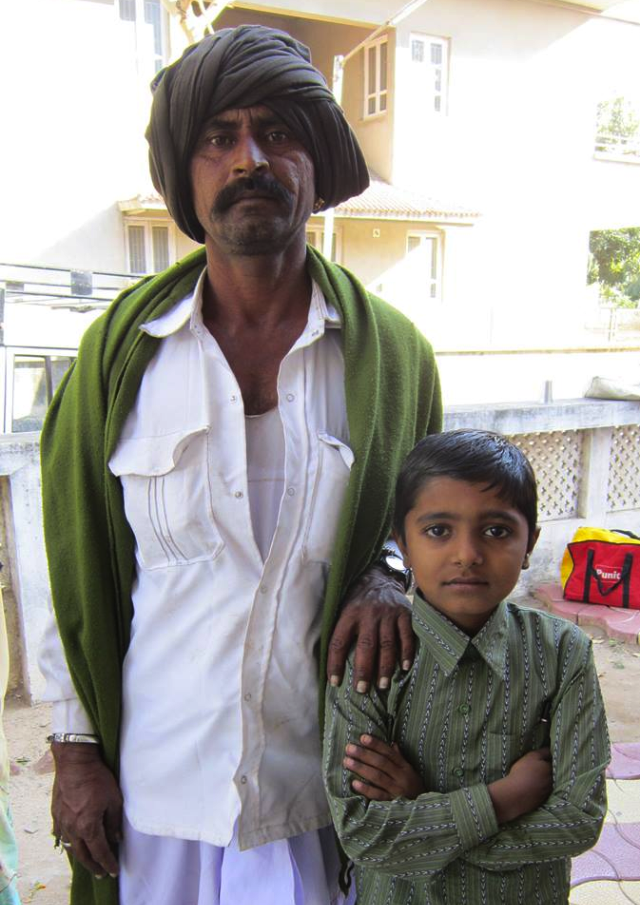

The children here come from a variety of backgrounds. We got to meet many of their relatives when a government official called everyone to the Home to announce some new regulations. One single mother sells fruit on the street, a single father is a shepherd, several had been cared for by aunts, uncles or a grandparent, and some had no relatives to call. All seem quite well adjusted to their new family of caring staff and vibrant children. Those who could were excited to introduce their relatives and have their picture taken with them.

We are spending a fair amount of time travelling back and forth to the construction site to check things out and especially to do the ground-work for the new bio-gas plant and water stabilization tanks. These will not only sanitize human wastes, but also provide about a third of the cooking gas for the Home and enough water to grow the large garden being planned to off-set food costs.

The man who came along to over-see this lay-out, from his home in Maharashtra, is one of India’s national treasures, Dr. Suhas V. Mapuskar, a member of Child Haven’s All-India Board of Directors. An octogenarian, he told us how as a young doctor in the 1960’s he was assigned to a small village. Upon his arrival he was mortified to learn there were no latrines at the health center, or anywhere else in the village. He was given a small pot of water and pointed out to the fields to answer nature’s calls. He also quickly found that much of the sickness he was treating resulted from open defecation and poor sanitation. This began for him a life-long passion for community sanitation and waste management. He discovered that 86% of the villagers had worms, and to treat everyone would cost 10,000 rupees, but that the worms would soon return without changing sanitation practices. On the other hand, a simple pit latrine cost about 400 rupees to construct. So he set to work. He laughingly recalls how the first 10 latrines he built using a World Bank pamphlet based on North American designs collapsed during the first rainy season. Subsequent latrines often ended up being used as convenient goat houses, shrines or storage sheds. He persevered though, and using a microscope to show people the worms they were dealing with, the importance of community sanitation became better understood.

Much of his early work was based on the pioneering work of one of Gandhi‘s co-workers, Appasahebe Patwardhan, who designed the first bio-gas system based on the use of human manure. Gandhi had been interested in waste management as part of his focus on raising the status of India’s “untouchable” caste who were often made to empty latrines for those in “upper” castes. Bio-gas systems turn human and other types of manure into cooking gas and garden fertilizer, doing away with the need to empty latrines. Over many years, Dr. Mapuskar has further evolved this system, and last year started the first Sanitation and Environment Training Institute at a university in Maharashtra, India. The Institute will attempt to address what Dr Mapuskar considers a woeful lack of awareness even among Indian engineers and architects of alternatives to the septic systems that are in Dr Mapuskar’s opinion one of the most inappropriate “gifts” brought to India by the British. They require huge amounts of increasingly scarce water, and most often drain into increasingly polluted streams, rivers and lakes. I asked Dr Mapuskar if it was Gandhi’s influence that helped draw him to sanitation issues. He replied that “at that time we were all mad after Gandhiji” and that his ideas are more relevant today than ever. “At present, oppression and unemployment are rising fast”, and that these problems are increasing due to unsustainable “development” and the abandonment of the village and rural economy so important to Gandhi. “Villages need to be revitalized” he states emphatically. His institute will address these and other most timely issues. We are hoping to establish a scholarship program for Child Haven university graduates to attend the Institute and further this important work.

Dr. Mapuskar in the middle of pointing out the layout of the biogas plant. I have only seen the Doctor wearing khaki, the homespun clothing inspired by Gandhi.

The bio-gas system at the new Gujarat Home will save Child Haven 50,000 rupees a year in cooking gas, along with supplying pathogen free garden water and compost. Under Dr. Mapuskar’s guidance, all our Homes in India are equipped with these systems. We are most fortunate to have the good doctor’s advice and counsel. For a little more about Dr. Mapuskar, Child Haven and our Homes in Gujarat see www.childhaven.ca

Next stop, the world headquarters of Child Haven International in Maxville, Ontario, Canada!

Until next time,

Robin Cappuccino for CHI

Thanks Robin for a very fun and informative look at the Child Haven International homes and projects through your eyes! We appreciate you sharing with us.